An Honest Look at Global Debt

• 11 min read

- Brief: Global Economy

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive an email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In the years leading up to the Great Recession, developed countries like the United States were responsible for the vast majority of global debt issuance, while emerging economies like China issued significantly less. From 2000 to 2007, global economies issued a combined $37 trillion of household, corporate and government debt, with nearly four-fifths coming from developed countries.1 This buildup of debt—particularly household and corporate debt—contributed to the severity of the financial crisis.

Since the credit crisis began in 2007, the picture of global debt issuance has changed dramatically. Developed economies have taken on large amounts of government debt in an effort to prop up their markets, but have issued relatively little on the household or corporate side. Emerging economies, on the other hand, have significantly increased their issuance of household and corporate debt. Emerging market corporate debt poses particular risks as it often takes the form of external debt owed to foreign parties, which at certain levels can contribute to slower future economic growth, higher inflation, and greater potential for financial crises.

Despite rising global debt levels, record-low interest rates have kept the costs of debt service manageable in most countries around the world. In fact, relative to national income, many countries’ total debt service costs are near historic lows. The ability of borrowers to service and repay their debts is also reflected in low loan delinquency rates, which in developed countries like the United States remain below historical averages across all loan types.

Global debt levels appear manageable in the current low-interest rate environment. However, AMG is carefully monitoring the risks of rising debt in emerging markets like China, as well as the potential for higher global borrowing costs, which would make debt more expensive to service. In the United States, growing U.S. budget deficits in the coming years and expectations for rising inflation could lead to higher interest rates across the domestic economy, reduced availability of credit to the private sector, and eventually slower economic growth.

In this context, AMG recommends investors be selective amongst non-China emerging markets and consider the potential impact that rising long-term interest rates and inflation expectations could have on domestic monetary policy and the U.S. economy going forward.

THE GLOBAL DEBT PICTURE

In the years leading up to the Great Recession, developed economies2 like the United States issued large amounts of household debt in the form of mortgages, credit cards, and consumer loans, as well as significant amounts of corporate debt in the form of corporate bonds. This buildup of debt contributed to the severity of the financial crisis that began in 2007.

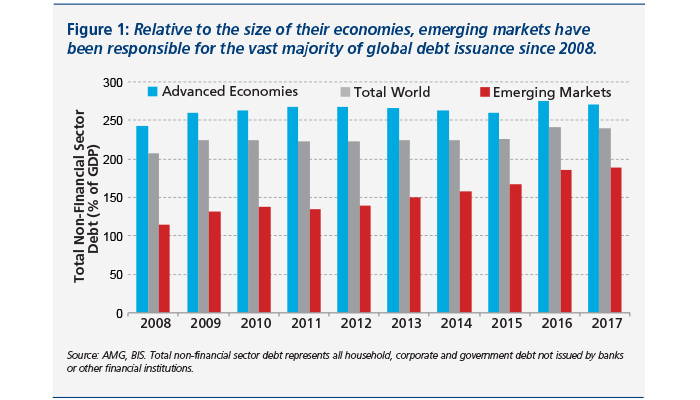

Since then, developed countries have taken on government debt in an effort to stabilize their economies, while emerging countries3 have issued large amounts of household and corporate debt. In spite of rapid economic growth (as measured by gross domestic product—GDP), emerging markets have increased their total debt-to-GDP ratio by 70 percent over the past decade (Figure 1).

THE TYPE OF DEBT MATTERS

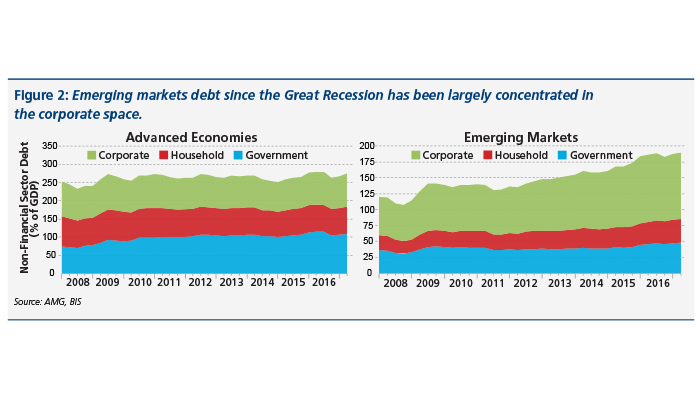

According to a 2014 study from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the amount of government debt outstanding in a country is important in determining how its economy recovers from a financial crisis, but buildups of household and corporate debt have historically contributed to financial crises in the first place.4 Thus, while emerging markets have issued a significant amount of total debt relative to the size of their economies in recent years, the high proportion of household and corporate debt raises particular concerns (Figure 2).

Corporations in emerging markets often rely on debt issued to foreign parties—or external debt—to finance their activities. Not only does external debt open a borrower to currency risk if the debt is denominated in a foreign currency, but high levels of external debt in emerging economies have also been associated with slower future economic growth and higher inflation. A 2010 study found that when external debt in the average emerging economy reaches 60 percent of GDP, annual growth declines by about two percent, and at higher levels of external debt growth declines further and inflation rises sharply.5

The prevalence of external debt in emerging markets differs by region. Developing European countries tend to have very high levels of external debt denominated in Euros, while some Latin American countries have issued large amounts of external debt denominated in U.S. dollars. At the end of 2016, some European emerging markets like Bulgaria already held more than 60 percent of their GDP in external debt, while Latin American countries like Colombia and Mexico had surpassed 40 percent. Other key emerging economies to watch are Malaysia and Russia, which had external debt equivalent to more than 70 and 40 percent of their GDPs, respectively, as of the end of 2016.6

AMG believes that China is also a potential concern. While China holds relatively little external debt relative to its GDP (just over 13 percent as of 2016), its total outstanding debt increased from less than 150 percent of GDP ten years ago to more than 250 percent as of June 30, 2017. Of this amount, over 200 percent was attributable to household and corporate debt alone. It is worth noting that a significant share of corporate debt in China is issued by state-owned enterprises, which are backed by the Chinese government and thus have a much lower risk of default. Nevertheless, and in spite of China’s strong economic growth and ample monetary reserves, the country’s debt buildup could eventually lead to further need for regulatory reforms and slower future economic growth.

COST OF DEBT SERVICE IS LOW WORLDWIDE

While rising debt levels do present risks to the stability and growth of economies, what ultimately matters for the health of the financial system is borrowers’ abilities to service their debts (pay interest and principal on time). Since the recession, global central banks have pushed interest rates to record-low levels in an effort to stimulate borrowing and lending in their economies. These record-low interest rates have also allowed borrowers to take on more debt than they would otherwise be able to by keeping the cost of interest payments low.

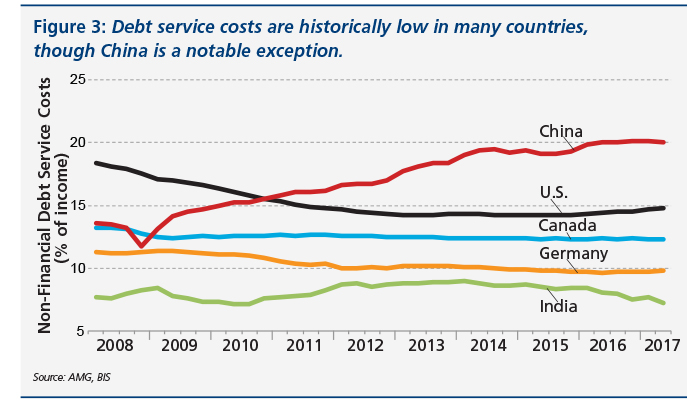

As Figure 3 illustrates, low interest rates have kept debt service costs subdued around the world relative to borrowers’ incomes. In fact, despite rising debt levels, the costs of debt service in many emerging and developed economies are near historic lows. China is a notable exception: debt service costs in China have increased from 14 percent of income to more than 20 percent of income over the last ten years. A significant portion of China’s debt service costs may again be attributable to state-owned enterprises, but nonetheless the rapid increase in total debt service costs relative to income bears watching.

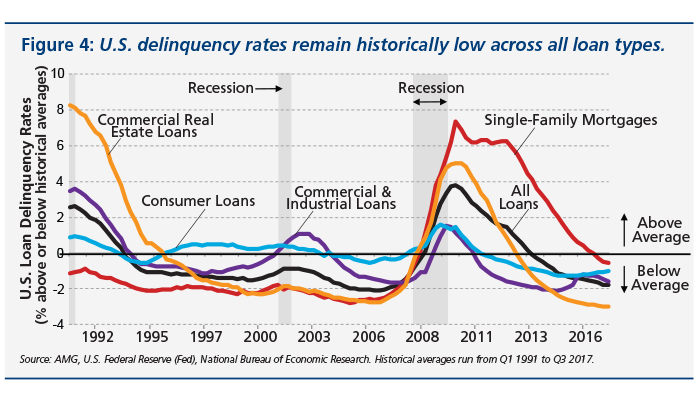

The ability of borrowers to stay current on their debt is also reflected in loan delinquency rates, which measure the share of borrowers that miss debt payments. As with debt service costs, delinquency rates are currently low relative to history in many countries around the world. As shown in Figure 4, delinquency rates in the United States remain below historical averages across all types of loans.

Ultimately, the impact of rising global debt levels has been dramatically lessened by record-low interest rates, which have also helped keep delinquency and default rates low. Even in emerging markets like China, AMG does not believe there is an immediate risk of a credit crisis as a result of elevated debt levels. However, this may all change when global interest rates begin to rise.

IMPACT OF RISING U.S. DEFICITS

In the United States, the Federal Reserve (Fed) began slowly increasing its short-term Fed Funds rate in December of 2015. The Fed Funds rate encourages or discourages overnight lending amongst banks and sets a benchmark for short-term interest rates across the U.S. economy.

In reality, market interest rates like those on mortgages and corporate bonds are more often based on long-term interest rates, such as the benchmark ten-year Treasury yield. An increase in the ten-year Treasury yield has the ability to raise borrowing costs across the entire U.S. economy and can directly impact the financial health of domestic households and corporations. Long-term interest rates only loosely follow the Fed Funds rate and tend to be more subject to market forces, including the supply of and demand for U.S. debt, demand for the U.S. dollar, and expectations for future growth and inflation.

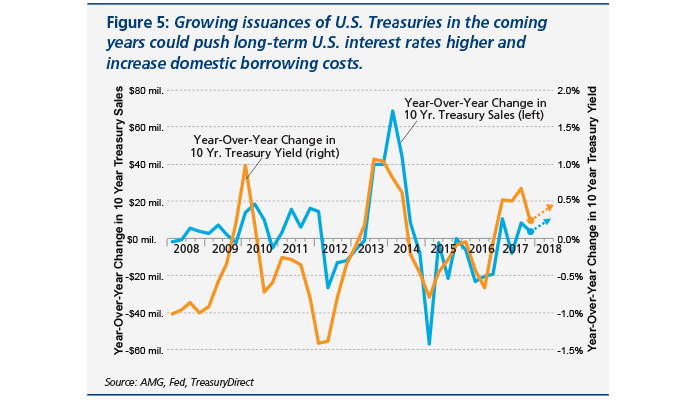

Inflation expectations have moved higher in the United States since late 2017, which has helped lift the ten-year Treasury yield to levels not seen for four years. Recent U.S. tax cuts, protectionist trade policies, and plans for future infrastructure investment have all contributed to expectations for faster inflation going forward. Together with growing entitlement spending on Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare, the tax cuts and infrastructure proposals will also lead to larger budget deficits in the coming years, resulting in greater issuances of U.S. Treasuries. As Figure 5 illustrates, increases in the supply of ten-year Treasuries often accompany increases in the ten-year Treasury yield, and could drive up borrowing costs throughout the U.S. economy.

INVESTMENT IMPLICATIONS

Debt levels currently appear manageable due to record-low interest rates around the globe, but borrowing costs are beginning to rise. The United States has already seen key market interest rates increase, and expectations are that the Euro Area and other major economies may be soon to follow.

In emerging markets, the prospect of higher interest rates and rapid increases in household and corporate debt raise concerns about future growth slowdowns or financial crises. China is one of the most prominent risks given its central role in the global economy.

In this context, AMG believes investors should be selective when investing in emerging markets, as potential debt risks are widespread. AMG also recommends focusing on emerging markets that are relatively insulated from the Chinese economy, because China’s high corporate debt levels and the ongoing efforts of authorities to slow credit growth could threaten its emerging market trading partners. A few countries that may be more insulated from China going forward are Vietnam, India, and Indonesia. Investors should also look for emerging markets with strong current account balances and ample foreign exchange reserves, both of which help provide a measure of protection against financial crises.

In the United States and across much of the developed world, debt has already reached historically elevated levels, but the prospect of rising interest rates presents additional risk. As the cost of debt service increases, the burden of any new or variable-rate debt will increase as well. Ultimately, this could mean higher delinquency and default rates on U.S. dollar loans, a clamp-down on borrowing and lending in the U.S. economy, and slower economic and corporate profit growth.

Rising interest rates and inflation expectations generally do not bode well for bonds. AMG recommends that bond investors focus on short-duration securities, as prices of those securities will be less sensitive to future interest rate increases. Rising borrowing costs and inflation expectations may also negatively impact stock prices in the short run, though certain industries (like financials) could stand to benefit from the higher interest rates.

Ultimately, AMG recommends investors be aware of the potential risks from emerging and developed economy debt in the context of rising borrowing costs and avoid the areas where rising debt levels present the greatest risk to economic growth and stability.

Notes

-

Source: Haver Analytics, National Sources, IMF World Economic Outlook, Bank for International Settlements (BIS), McKinsey Global Institute.

-

Developed economies as defined by BIS include Australia, Canada, Denmark, the euro area, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

-

Emerging economies as defined by BIS include Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Hong Kong SAR, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand and Turkey.

-

Òscar Jordà, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. “Private Credit and Public Debt in Financial Crises.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 10 Mar. 2014, www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2014/march/private-credit-public-debt-financial-crisis/.

-

Carmen M. Reinhart & Kenneth S. Rogoff. “Growth in a Time of Debt,” American Economic Review, American Economic Association, vol. 100(2), pages 573-78, May 2010.

-

Source: World Bank data.

This information is for general information use only. It is not tailored to any specific situation, is not intended to be investment, tax, financial, legal, or other advice and should not be relied on as such. AMG’s opinions are subject to change without notice, and this report may not be updated to reflect changes in opinion. Forecasts, estimates, and certain other information contained herein are based on proprietary research and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any particular security, strategy, or investment product.

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.